This story originally appeared on the Gents Cafe Newsletter. You can subscribe here.

New York tells its story not only through skylines and avenues, but through its smaller, humbler stages: the corner shops where lives cross and traditions endure.

Coming from a background in the arts, Joel Holland refined his distinctive drawing style over the years, with his illustrations appearing in The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, and even in Apple store windows across the world.

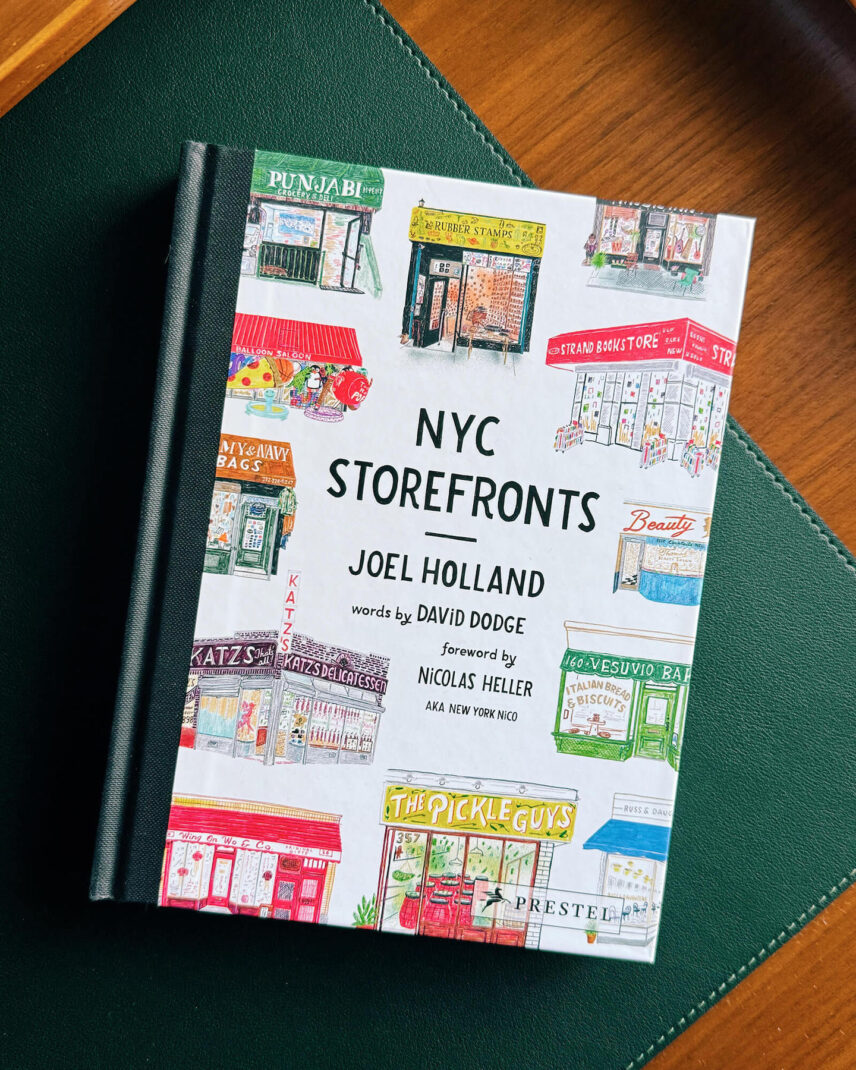

With NYC Storefronts, his illustrated coffee table book, Joel turned a series of sketches shared on his Instagram profile into something larger: a love letter to neighborhood shops and the communities they anchor. His work reminds us that culture is not only in museums or theaters, but also in the corner bakeries, jazz clubs, and bodegas that frame our daily rituals.

In this Scent of Paper interview, Joel speaks about the intimacy of these places, the stories that surprised him most, and how illustration became his way of honoring the fragile permanence of local life.

When did you first start drawing—and when did it become clear that illustration could be more than just a passion?

I’ve got two young daughters, and right now they’re at that age where art is still really encouraged in school—drawing is something they do all the time. This makes me think back to my own childhood and realize I was the same. I drew casually, for fun, but never once thought of it as something that could become a career. I don’t even think I had the concept of illustration as a profession.

Luckily, my college had a really broad arts program—design, photography, drawing, printmaking, sculpture—so I got to experiment a lot. Over time, drawing and illustration started to stand out.

What really sparked it was my love of book covers—the lettering, the illustrations, the whole package. But at that point, in the late ’90s, I wasn’t sure where I fit. Gradually, I realized illustration was my lane. I started working with magazines and books, and the hand-lettering side of things opened a lot of doors—book designers would hire me to do both lettering and drawings, which was a perfect combination. That’s when it really clicked: this was what I wanted to do, and it could actually sustain me.

You’ve lived in New York City for over two decades. How has your relationship with the city evolved over time?

I grew up in rural Pennsylvania, but from early on—through basketball, hip-hop, jazz—I knew I wanted to be somewhere else. New York felt like the place. I moved here in ’98, lived in Brooklyn for about 15 years, and just absorbed everything. Even small things, like the guys at the bodega across the street from my apartment—how they’d shift their chairs with the sun so they always stayed in the shade—that kind of everyday rhythm really stuck with me. Same with places like Julio’s, a little lunch spot I could see from my window. Watching the line of workers form every day made me want to draw it. In a way, that’s where the storefront project started.

When we had kids, we moved into Manhattan. It’s a different energy—Brooklyn feels calmer, Manhattan keeps you “on.” Both have shaped the way I see the city. Over time, I’ve realized these projects force me to ask why certain places matter. Some spots are part of your daily routine, others you love but don’t get to enough, and some you never quite reach. I’ve wanted to celebrate all of them—to help them feel seen, and to remind people how important they are to their neighborhoods.

You began drawing storefronts during the pandemic—almost like a visual love letter to your favorite places and neighborhood spots. Sharing them on Instagram quickly sparked a wave of appreciation. How did that community response shape the evolution of the project? And when did the idea of turning it into a book first take shape?

I know social media gets a bad rap—much of it deserved—but honestly, none of this would have happened without Instagram. During COVID, my work slowed down and I needed something to keep me busy. My kids were doing school from home, so while they worked, I’d sit at the table and draw. I posted one of those drawings just to stay active, and the response was immediate. It felt good—not just for me, but because it seemed like people really connected with it. That led to more drawings, then more posts, and pretty soon I was doing one a day.

The community response really shaped it. People started suggesting places: “You should draw this spot,” or “Don’t forget about that one.” I couldn’t do them all, but a lot of the suggestions were great. At the same time, I was connecting with others who were documenting the city in their own way—like New York Nico with his videos, or artists making miniature storefront models. There was this whole shared energy of people trying to celebrate and protect what makes New York special.

And then there were moments that made it feel urgent. Around that time, anti-Asian violence was rising in the city, and I felt compelled to support Chinatown. Other times, I’d hear a place was closing or launching a Kickstarter, and I thought, “If I do a drawing, maybe it’ll help.” So the project quickly became about more than just staying busy—it felt like a way to contribute.

By the time I’d drawn around 200 storefronts, I thought, this should be a book. I’ve always loved books, and I reached out to publishers and agents, but kept hearing no—too niche, too New York. I was close to self-publishing when I got a message on Instagram from Ally Gitlo, who’s now my editor. She asked if I’d ever thought about making it a book. I said, “Funny you should ask…” and sent her my proposal. She immediately got it, had the same energy I did, and things moved quickly from there.

We brought in the writer David Dodge, whose witty essays brought a whole new layer to the drawings, and Alex Stik Leather, a fantastic designer who pulled everything together beautifully. The first time Ally sent me cover options, I teared up. Seeing my name on something that looked so good—it felt unreal.

What started as a few sketches at my kitchen table turned into this book, and I feel so lucky to have been part of a team that made it happen. It’s a reminder that even in tough times, something small—like sharing a drawing—can snowball into something bigger than you ever imagined.

What did the recommendations you received reveal about the emotional bonds people form with local places?

It’s incredible. The recommendations I’ve received really opened my eyes to how deeply people connect with local places. Sometimes it’s organizations, like Neighborhood Spot, which helps small businesses create merch. Sometimes it’s just individuals sharing a story. But there’s always this energy—people pushing for each other, wanting these places to survive. That’s really powerful to me.

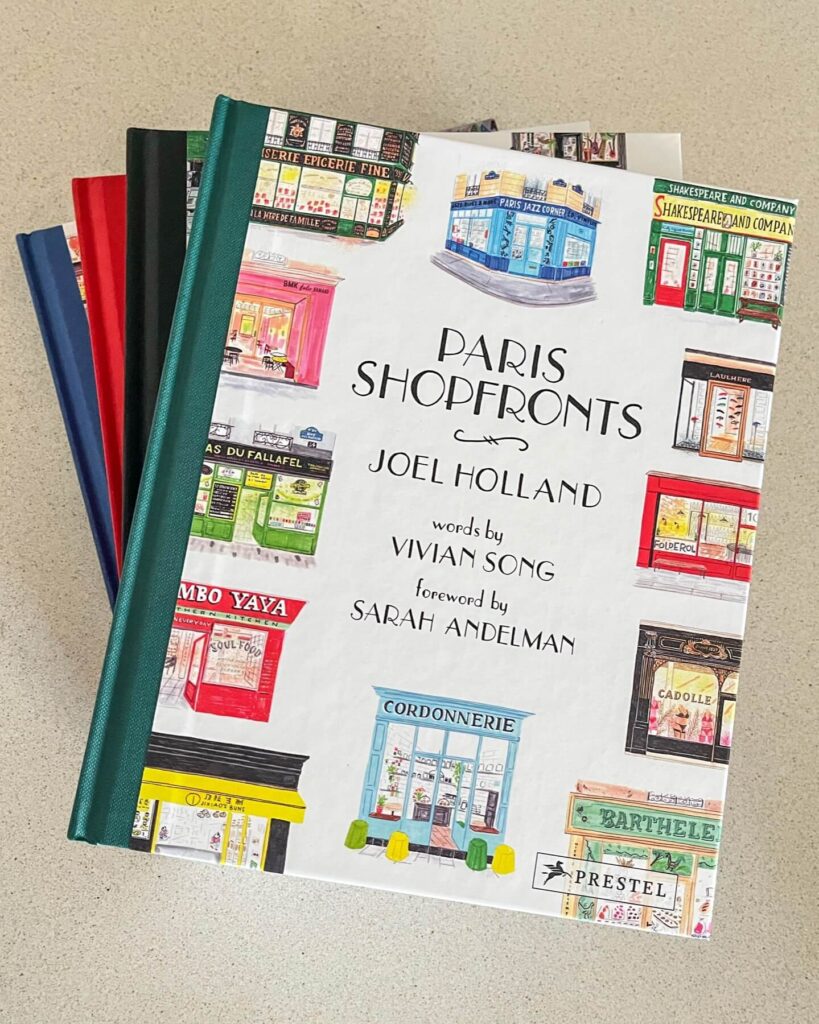

Having now done books on New York, Brooklyn, London, and Paris, it’s also fascinating to compare the feedback. The response from Paris was almost equal to New York—so much enthusiasm and pride. Brooklyn felt different, more intimate, more mom-and-pop. But in every city, the common thread is that emotional bond people have with their neighborhood spots.

Those stories are the fuel for me now—and sometimes the torture too. If someone tells me about a place with meaning, I feel compelled to draw it. And the stories aren’t always big dramatic ones; often they’re small but powerful. Someone misses their favorite coffee shop after moving away, or remembers a place where they always went on dates. Even something as simple as “this is where I get my bagel” carries weight.

When I travel, I notice it in myself too. As soon as I’m back home, I want to check in with my places, say hi to the people, feel grounded again. That’s what makes these spots so important—they’re more than businesses. They’re touchstones in people’s lives.

Your illustrations capture a side of New York that feels intimate and local. In your view, what role do small shops play in shaping the soul of a community in a city like New York?

It’s priceless. Small shops are everything—they’re what make up the rhythm of daily life. Sure, you can go to a museum for culture, and that’s important, but what about the coffee you grab on the way there? Or the drink you get afterward? Those everyday stops, whether they’re planned destinations or just the places you pop into, hold immense value.

When I talk about these books, I always say it works two ways. Yes, you should absolutely go to Katz’s Deli, which is on the cover of the New York book. It’s iconic and worth the trip. But it’s also about appreciating the deli on your corner, the one you might overlook. Supporting those neighborhood spots matters, because if they disappeared, where would you get your coffee, your groceries, your little daily essentials?

It’s about recognizing the ecosystem you’re part of. When you move—even just a few blocks into a different neighborhood—your whole solar system changes. Your routines, your touchpoints, the people you see. That’s the soul of the city, and it lives in those small shops.

When a storefront really stays with you, what is it that leaves a mark—the design, the story, the people behind it?

It’s usually a mix. At first, if I don’t know the place yet, it’s the visuals that grab me—the signage, the lettering, especially if it’s hand-painted. That’s probably what clicks with me first. Then it’s the content: what kind of place is it? And it doesn’t have to be food. That’s what I love about this project—it can be a restaurant, but it can just as easily be a bookstore or a shoe repair shop.

But none of that matters without the story. A place can look great, but if there isn’t something deeper behind it, it doesn’t hold the same weight. That’s what I really enjoy about working on the books with our team, or even just deciding what I want to draw—asking myself, why this place? What’s behind it? Who’s behind it?

In the end, it’s all about soul. The order in which I notice things might change—the sign, the story, the people—but if a place has lasted long enough to be considered for the book, then it already has soul. My job is just to try and capture it.

While working on the book, was there a particular story behind one of the storefronts that really surprised or moved you? Something unexpected you discovered while speaking to the owners or researching the place?

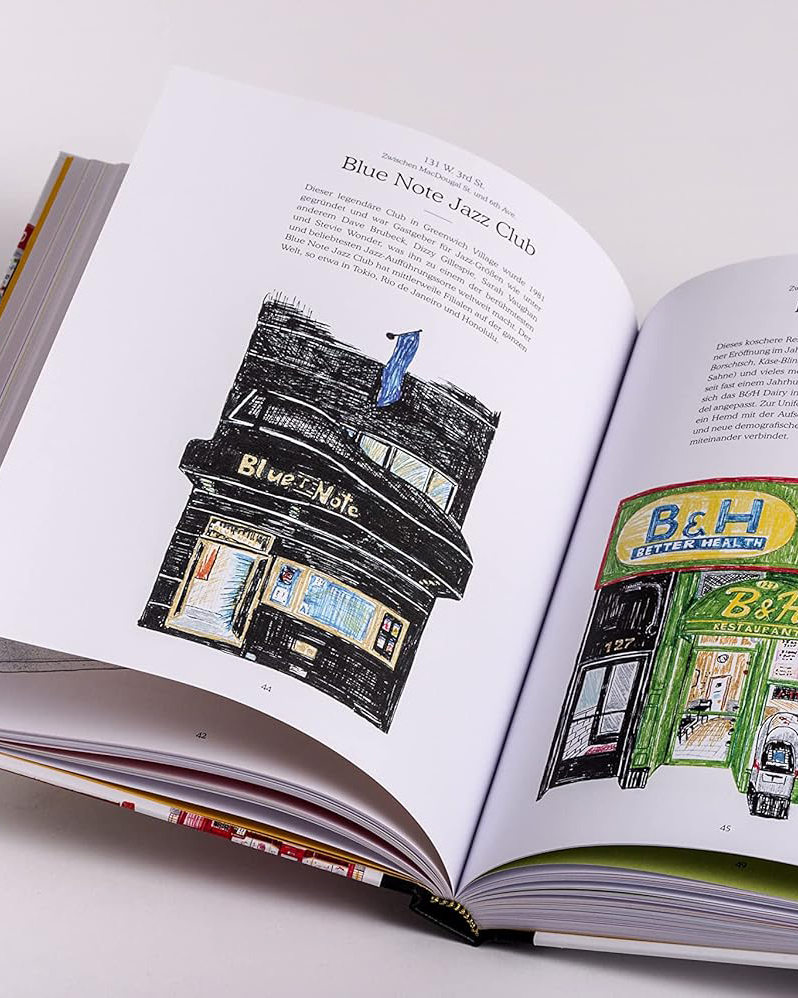

For me, the surprises usually come after the fact—when David sends over the text he’s written to go with one of my drawings. I’ll find out that a place I liked simply for its look, or because I’d heard a jazz musician used to hang out there, actually has this whole other history—like tunnels running into the East River. Those are the kinds of things I’d never know until I read his work.

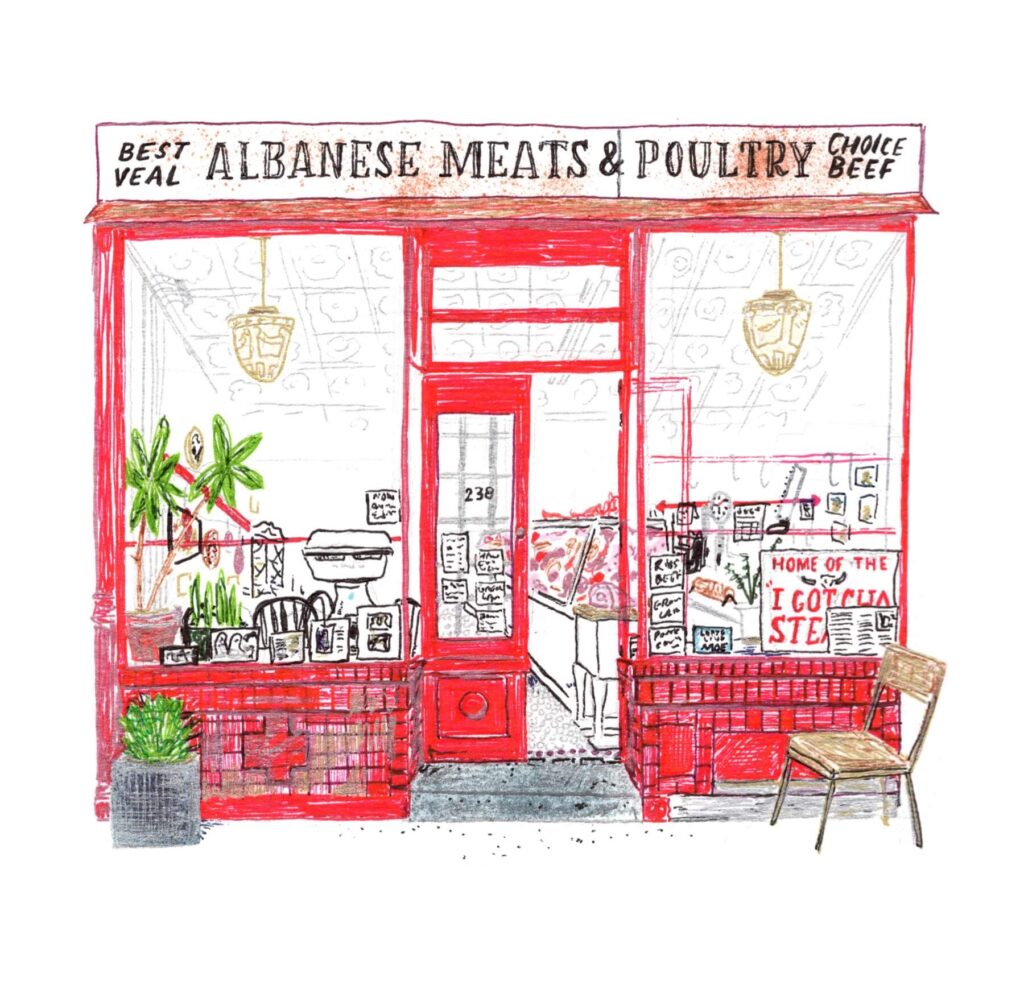

One story that really stuck with me is Albanese Meats, a hundred-year-old butcher shop in Soho. The current owner, Jen, started working there when her grandfather—who was in his 90s—was still running it. He passed away during COVID, and she ended up taking over even though she had other plans for her life. I didn’t know her at all when I first drew the shop, I just thought the exterior was beautiful. I posted it, and she reached out.

We ended up visiting, buying meat there, and eventually becoming friends. She even came to my New York book launch. Now when I stop by, we don’t just talk about the store—we talk about our kids, travel, everyday life. She’s even shown me parts of the shop nobody else gets to see, like the old cooler in the back with its original tile floor.

Moments like that are the best part of this project. A simple drawing turns into a real connection, and suddenly I’m not just documenting a storefront—I’m part of its story too.

Independent shops often carry a sense of ritual—your daily coffee, your favorite slice. Do you think we’re collectively rediscovering the value of physical space, especially in the age of online everything?

That’s a tough one, because I think it really depends on where you are. I grew up in a small town where there was just one gas station, so that’s where everyone went—no options, no rituals, just necessity. In a city, though, you have endless choices, and that’s where those daily routines and attachments really take shape.

I do think people have always valued that, but what feels different now is how it’s being expressed. Over the past five or ten years, it’s suddenly become way cooler to wear merch from your favorite pizza shop, your local bar, your neighborhood restaurant. That kind of pride in a small business feels more visible than it used to be.

Maybe Instagram has something to do with it too—people want to take photos at beautiful storefronts. And hopefully it’s not just about the picture of themselves, but also about boosting the shop and actually supporting it. My sense is that there is more awareness now, more attention being paid. And if that translates into people showing up, buying something, keeping those places alive, then that’s a good thing.

How did you decide what the location of the second book should be, and what does the research process look like?

A lot of the decision-making comes down to the publisher. They’re based in London, so the second book ended up being London—that was their idea. The third one was Brooklyn, which made sense because I had already drawn around 50 shops there, so I had a head start. I knew Brooklyn would work as a book. And with each one, I think the breadth and comprehensiveness have gotten better. Then the publisher suggested Paris. I’ve pitched other places too, but they haven’t been as excited about those yet.

As for the research, by now we’ve got a bit of a formula. Not literally in terms of specific types of businesses, but in terms of balance: you want some of the weird, old spots, the really popular, famous places you have to go to, and then the opposite—fresh places that maybe just opened but already have a great story. The key is that they have to be established enough that they won’t disappear overnight, because once they’re in the book, you want people to be able to go there.

So we work with local writers to pull those lists together. And beyond that, the weirder and more diverse, the better: women-owned, immigrant-owned, all of that adds richness. The writers bring us a big list, we edit it down, and then I start drawing. Every once in a while there’s a place that’s too complicated to draw, but most of the time it’s just a back-and-forth until it clicks.

From Brooklyn to Paris to London, you’ve explored the character of cities through their small shops. What surprised you most about how different cities express themselves through their local shops?

Honestly, the thing that’s stood out the most is how universally positive the response has been. People everywhere love their local shops, and that energy—“we appreciate this, we love this place”—is what keeps me going. I’ve drawn somewhere between 1,200 and 1,500 storefronts now, and I still love doing it.

What is one of the most interesting feedback that you receive from a reader of your book, so not one of the shop owners that you feature?

One of the most interesting pieces of feedback came from a reader completely separate from the shop owners. Early on, before the New York book, I had drawn a little push cart in Chinatown selling “yummy cakes”—mini pancakes the size of a wine glass base. Later, when I reposted that drawing, someone messaged me saying, “My god, that was my dad’s place. I live in Hawaii now, but still remember it vividly.” That kind of personal connection really hit me.

Another time, I was at the Blue Note Jazz Club with my oldest daughter. The next day, a place I follow on Instagram, Lloyd’s Carrot Cake, posted a photo from the exact same angle I had been sitting at. I reached out, and it was this fun, small connection: “You were the person next to me at the show last night.”

The most memorable, though, was with Ricky Powell, the photographer who was kind of the fourth member of the Beastie Boys. I had drawn Bigalow Pharmacy in the West Village, and out of the blue he reached out, saying he wanted one of my pieces. We started trading messages, joking and bantering for months. He even asked me to draw a place he used to go with his grandma. Unfortunately, he passed away before we could finalize it, but I still have the drawing—it’s precious.

These moments are amazing because they show that people carry memories in these places, and my drawings somehow connect with them. It doesn’t matter who they are, it’s the stories and memories that resonate. That’s the coolest part of all of this.

What would you say is the most fulfilling feeling or thing you’re getting out of this whole project?

It is definitely when someone from the business sees a drawing of their place and really connects with it. A great example is Jen at Albanese Meats. When I gave her the drawing I had made, she immediately noticed the small details—the chopping block, the old scale, little things from the window display. She recognized them and also felt the history of the store, her grandfather, everything tied to it.

Knowing that my work can create that kind of emotional connection, even just a moment of joy or nostalgia, is one of the coolest things about this whole project. It’s not just about the illustration—it’s about capturing the soul of a place and having that resonate with someone who lives it every day.