This story originally appeared on the Gents Cafe Newsletter. You can subscribe here.

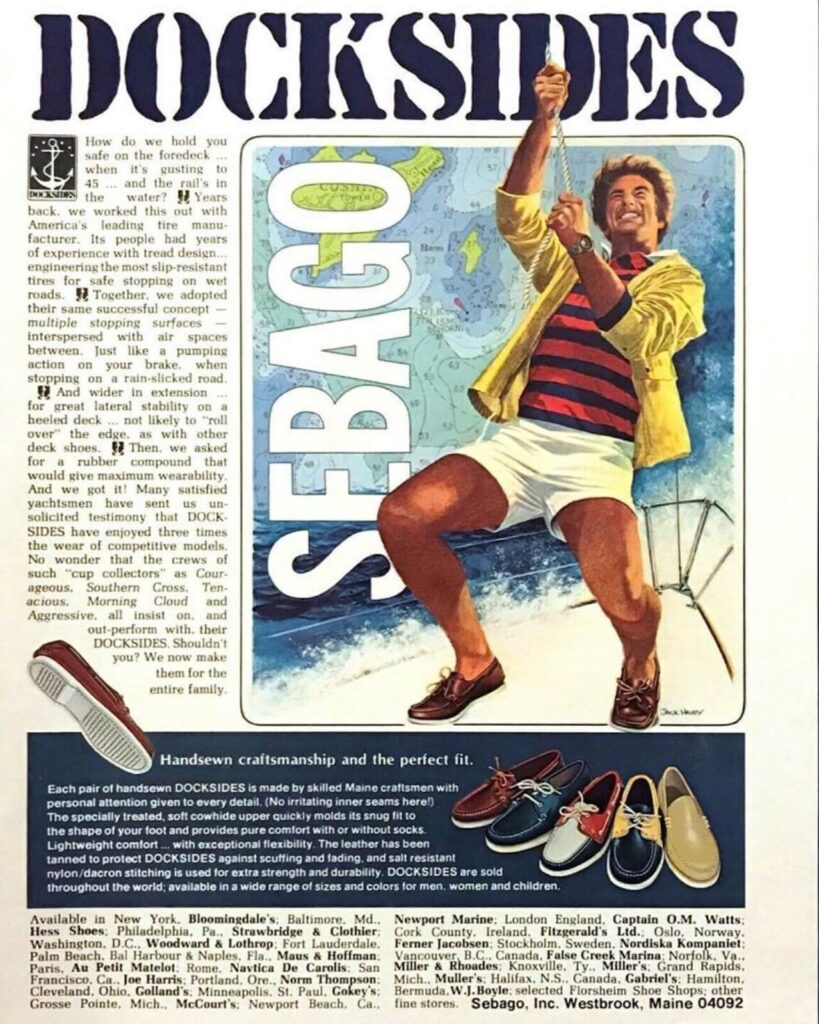

Born in Portland, Maine, Sebago left a lasting mark on the history of American footwear, becoming synonymous with timeless classics like the Penny Loafer and the Boat Shoe. In 2017, the brand entered a bold new chapter when it was acquired by Italian group BasicNet, which breathed fresh life into its heritage.

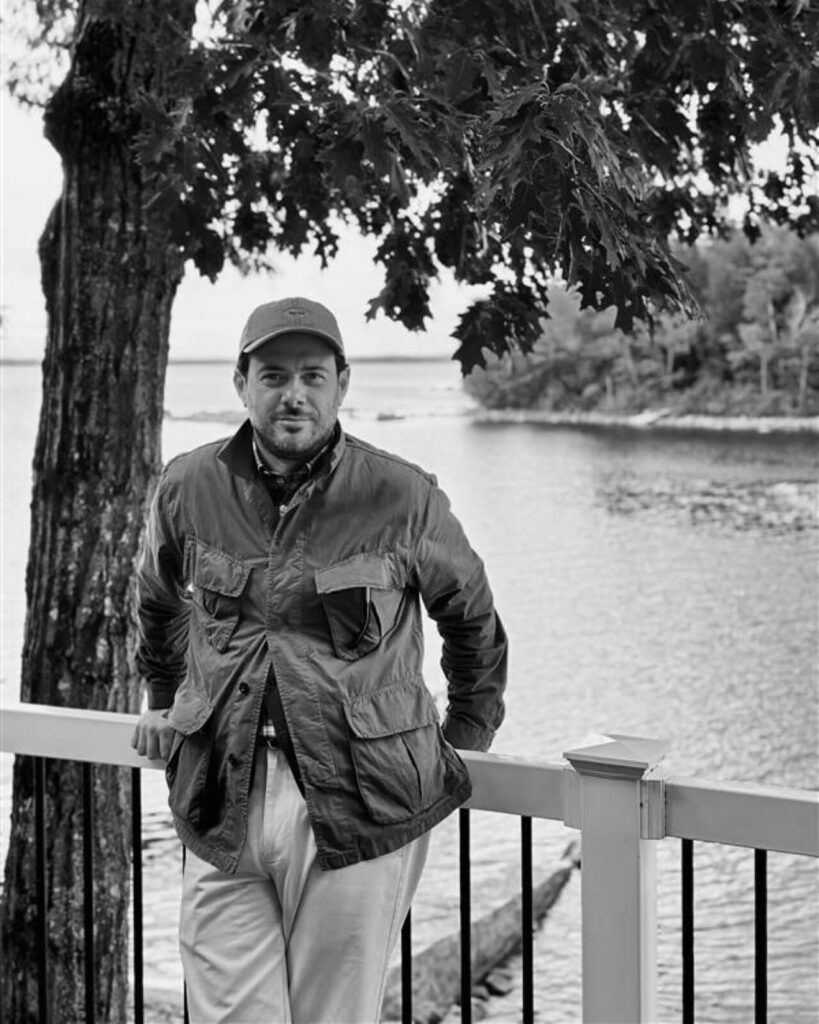

At the helm of this revival is Marco Tamponi, Global Brand Manager and menswear connoisseur, whose vision has reaffirmed Sebago’s relevance in contemporary footwear, while successfully expanding the brand’s universe to include a total look collection of shirts, trousers, and accessories, all designed with a refined sense of outdoor living.

In this Brand Talks interview, Tamponi reflects on his personal journey – from a background in sociology to a rich career in fashion and sales – and offers a thoughtful perspective on Sebago’s enduring philosophy, its evolution, and what lies ahead.

Could you tell us about your background?

My biggest luck – and something I always try to share with my team – is having managed to turn my passion into my job. I fell in love with menswear around the age of 16, especially the Anglo-American world, and even more so, the American one. I started traveling to the U.S. and collecting American vintage – military, workwear, preppy, Ivy – and I became fascinated with East Coast culture: hunting, fishing, that whole world. And of course, like many others, I was guided by the greats: Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers, L.L. Bean… That’s when I started collecting pieces, building a relevant (and never really organized) archive, back when you could still find vintage at flea markets and garage sales – before speculation took over.

Over the years, I worked in sales and brand management, mainly on the commercial side. Then, at around 25, I began working on brand creativity, especially for the European market.

It was actually in Japan that I discovered the true depth of American product history, since there it is preserved way more than in the U.S. itself. That insight allowed me to develop collections for the European market on behalf of American brands that often didn’t have a strong understanding of Europe – just as we, in turn, don’t always fully grasp the American market and its dynamics. My focus was always to bring out the heritage of these brands, because to me, that’s their real and only value, especially when you’re dealing with names that have 50, 60, even 70 years of history.

How did you become Global Brand Manager at Sebago?

In 2017, BasicNet – the company I work for today – acquired Sebago from a large American group. Since I was already working with brands connected to that universe, I was brought in to help revive Sebago. The brand had always had a strong presence in Europe, but it had somewhat faded in the past decade. Together with the team, we made the decision to stop thinking of Sebago as just a footwear brand and start building a lifestyle vision rooted in the American coast – which, in many ways, is the closest to our European culture. After all, it’s called New England for a reason.

That’s how this journey with Sebago began: for me, it felt almost natural. The brand aligns perfectly with my mindset – not just professionally, but personally as well. I’ve been with Sebago for six years now, and I have to say, it’s been an awesome journey. I believe we positioned the brand in the right way, and we also happened to ride a trend that worked in our favor. I’ve been part of this world for 20 years, and 15 years ago, it definitely wasn’t considered as cool as it is today. The Oxford button-down shirt, chinos, and boat shoes were the “uncle’s outfit”. But over the past five years, there’s been a huge wave of interest that pushed us even faster in the right direction.

How did you first develop a passion for menswear, and how does it keep you inspired in your work?

I think my passion comes from an interest in what clothing represents. I studied anthropology at university, and I’m deeply fascinated by the importance of formal codes in clothing. I believe it’s one of the first forms of nonverbal communication ever invented by humans. In fact, my thesis was about debunking a saying I consider not really accurate: “Clothes don’t make the man.” Of course they do! Just think about armies, subcultures, religions – ever since humans started wearing clothes, clothing has always had an enormous cultural and symbolic value.

It might also has something to do with my background: I come from a family with ties to the navy, so I’ve always had a certain sensitivity toward understanding the meaning of uniforms and, more broadly, the symbolic power of clothing. That’s why, from a young age, I tried to get as close to the product as possible – but always with a cultural approach, going to the roots, studying vintage. When I started collecting, vintage wasn’t a trend yet – it was a way of understanding where certain garments, and specific stylistic solutions, actually came from. I’ve always tried to study things seriously, to understand their origin.

Several trips to the U.S. with my family really opened my eyes to this world. I came back with a stack of catalogs from L.L. Bean and Ralph Lauren and that’s how it all started. For us Europeans, that world is aspirational: the vastness of America, its geography and culture, has always held a particular allure – sometimes even more than our own local culture. But after spending a few years in the States, I realized that what we receive in Europe isn’t the real America, but rather a romanticized version: a sort of “cocktail” of different concepts all blended together. Ralph Lauren, for example, would mix a yuppie, a Native American, a hunter, a fisherman, and an Ivy League student – and present them as one coherent world. But once you really start traveling across the U.S., you understand the difference between reality and narration.

While I was at university, I started working in a clothing store, then moved on to showrooms. I just knew that was the path for me. Back then, the access to design, marketing, or fashion communication schools was limited, and if you wanted to get close to the product, the easiest way was to sell it. So that’s how I got started; and at the same time, I was observing, trying on collections, studying garments. Travelling and meeting people from the same sector allowed me to build up deeper and deeper knowledge, always with a cultural approach at the core.

What’s your personal definition of style?

I believe that true style is rooted, first and foremost, in a strong sense of belonging – a connection to a culture, an aesthetic, a particular lifestyle. Fashion, especially in recent years, has become a fascinating world, but it’s moving in a direction that’s almost the opposite of what we do at Sebago – of the kind of style that represents genuine belonging.

For me, the real ambition when we create a product is to imagine it exactly the same twenty years from now, because it was never about being fashionable to begin with. And above all, to make something that actually gets better with time. Think about your wardrobe: there are garments that age beautifully, and others that simply wear out. The goal is to create products that become more beautiful over time – fading in a unique way, without losing value or looking worn-out and thrashed.

In the case of Sebago – and Superga, which I’m partly involved with as well – my deepest roots are in menswear. Menswear has clearly defined codes that evolve, adapt to the times we live in, but remain recognizable. And above all, they differ by geography: there’s American, British, Italian, European men’s style. Our goal is to never fall into the trap of “vintage.” Because there’s a huge difference between vintage and classic. Vintage belongs to a specific era, and outside of that context, it can feel forced. Classic, on the other hand, is timeless – whenever it’s worn, it still feels relevant in the present. Of course, classics evolve too – the materials today aren’t the same as in the ’70s or ’80s, and the lifestyle of the people wearing them has changed – but the essence remains unchanged.

And I can tell you that today, for us who don’t engage in greenwashing, that concept is the real starting point for sustainability. Personally, in the last twenty years, I don’t think I’ve ever thrown away a piece of clothing. I repair them, change the collars on shirts, fix shoes. Because the true environmental impact isn’t just about production emissions – it’s about how long a product lasts. These days, we see a lot of recycled materials, but they often require highly polluting processes to be produced, and the end result is something that barely lasts. If you have to throw it away and buy a new one every three years, you’re not solving the problem.

I recently spoke with a company that studies exactly this: the most sustainable object is the one that lasts the longest. Think about it – a Hermès bag is probably one of the most sustainable products in the world, because it’s passed down through generations, restored, repaired, resold. That’s the idea: to create objects designed to last, and to improve over time.

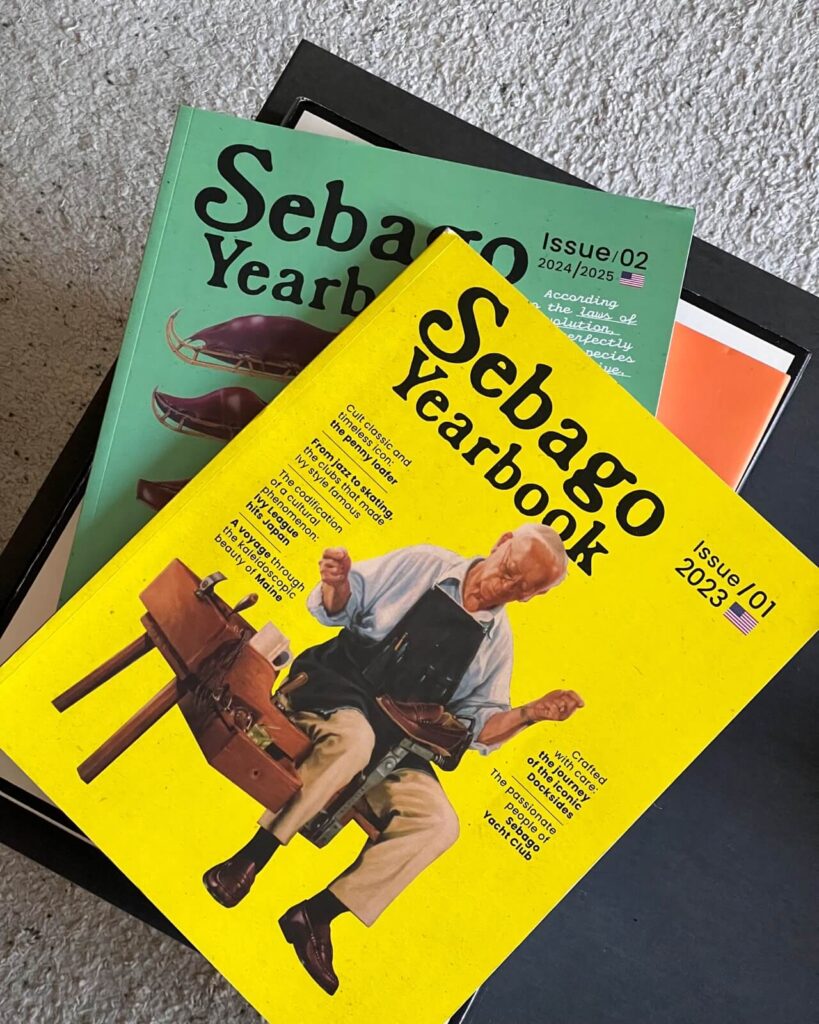

Back in November, you launched the second volume of the SEBAGO YEARBOOK, an editorial project that goes beyond the product and narrates the brand through images and stories. Where did the idea come from?

There were several reasons behind it, but one of the main ones – which I probably only realized later – was a kind of personal frustration. When you work with a deep, thoughtful approach, when every choice in terms of style, materials, storytelling, has a reason behind it, it’s disappointing to see that the message doesn’t fully reach the market. We build collections where every element is in dialogue with the others: a shoe connects to a pair of chinos, a chino pairs with a tie – everything has its place within a coherent narrative. Yet, too often, it all gets reduced to a single shoe sitting on a shelf.

Another reason came from my experience with social media. Early on, when I was involved in every aspect of the brand – from production to style to marketing – we created social content that, to me, felt perfect. But it didn’t perform. Too long, too complex. What was needed was immediacy – you had to get your message across in 30 seconds or it was “boring.” And for someone who approaches their work with depth and care, that’s hard to accept.

At a certain point, we realized we needed to put Sebago’s identity down on paper. But how? It couldn’t be a single brand bible, because Sebago isn’t a static brand – it’s constantly growing, enriched by new stories and new layers of meaning. So, inspired by American and Japanese editorial culture, the idea of an in-house editorial project was born.

The Sebago Yearbook isn’t a catalog – it’s a magazine that tells our story. I wanted an object with a slower rhythm, something you could revisit over time. My shelves are full of books and magazines: books you read once, but magazines you return to, flip through, discover new details. That’s what we wanted to create – a project without the constraints of a 15-second reel or a six-page brochure.

We handled every aspect of it in-house: I oversaw the creative direction, and our marketing department worked on the content. But we didn’t write it ourselves – that would’ve been self-referential. Instead, we brought in our community: experts who live this world and can speak about it with authority. David Marx, author of Ametora, who wrote about how Japan helped save American style; the Beams Japan team, Michael Hill from Drake’s, Mark Beaugé, and many others. It’s not a brand monologue – it’s a dialogue between people who share the same passion.

The final section of the book is a tribute to vintage American catalog culture – the ones we used to flip through as kids, full of chinos, blazers, loafers, sailing jackets. Of course, we reimagined it with a modern eye, because we’re no longer visually tuned to black-and-white pages from that era. But the idea remains the same: to convey the brand’s depth.

The response went beyond anything we expected. The first volume sold out, and when the second came out, demand for the first skyrocketed. We organized events across Europe – from Italy to France, Spain to Germany – to promote it. And what’s really interesting is that the Sebago Yearbook turned out to be a more powerful marketing tool than the collection itself. Because once you understand where everything comes from, the final product – the shoe, the chino – takes on a whole new meaning.

Right from the outset, Sebago has collaborated with some of the best brands to create limited editions. What’s the philosophy behind these collaborations, and how do you choose the right partners?

Collaborations, for us, are a way to build connections with brands that share our vision or can take us in new directions. We’ve partnered with Pendleton, the historic American blanket brand known for its Native American patterns; with Baracuta, famous for the classic G9 Jacket worn by Steve McQueen and Paul Newman; with J. Press, maker of the iconic Shaggy Dog sweaters loved by JFK; and with Drake’s, which to me represents the highest expression of English casual-formal style today.

Right now, we’re working on new projects. These partnerships reflect the professional network we interact with in our world – they’re born from cultural affinities and a shared passion.

Then we also have a different kind of collaboration, more commercially strategic, which allows us to take the brand into new territories. While brands like Drake’s, J. Press, Baracuta, or Pendleton tell a story similar to ours, there are other brands we collaborate with precisely because they come from very different worlds. These partnerships give us the freedom to explore spaces that, on our own, we might never reach.

The heritage of Sebago is deeply rooted in craftsmanship. How important is the concept of “hand made” in your vision of quality? And how do you communicate it?

The concept of “handmade” is a complex one to handle, but it’s still fundamental for us. Fortunately, there are still artisans behind every product, even if their numbers are declining. Take our shoes, for example: they simply couldn’t be made without a human touch. It’s a defining trait that preserves the craftsmanship behind our brand, but it’s also a practical necessity to achieve the fit and look we’re after, especially in the case of the loafer. Our shoes aren’t perfect, they’re “beautifully imperfect”, because that human element makes each pair unique. Every stitch hole on the apron is pierced by hand, by an expert craftsman with twenty years of experience, who instinctively knows where to puncture the leather based on its specific thickness.

That level of detail wouldn’t be possible with industrial machinery. But we have to acknowledge that craftsmanship is fading in this industry. That’s why we no longer manufacture in the United States, as was the case until the 1980s. We’ve moved production to Central America, where the U.S. transferred much of its know-how, and where the tanning and stitching techniques remain consistent with what we’ve always used. Countries like Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador have become strongholds of quality production thanks to their cultural and technical proximity to the U.S.

At the same time, craftsmanship isn’t required for every product we make. We want our world to be accessible to a broader audience, and striking a balance between artisanal work and industrial production is essential to staying competitive.

Over time, I’ve learned that a product’s value lies in how the consumer perceives it. If you overload it with unnecessary details or overly luxurious materials that your customer doesn’t understand or appreciate, you’re making a mistake. Early on, I used to want to go all out, but I realized I was wasting resources. Now, our goal is to make sure what we produce is understandable, accessible, and truly valued by our audience.

Sebago is more than just a brand: it is a cultural point of reference for many enthusiasts. Events in you flagship stores welcome influential figures of journalism and menswear, turning your boutiques into cultural hubs. What’s the goal of these activations, and how do they strengthen the bond between Sebago and its community?

Retail has become a key element of our business – a true storytelling tool and a way to shape the brand’s entire dimension. In our stores, we’ve found that our customers aren’t just shoe enthusiasts – they have a genuine affection for the brand. That’s why we offer a wide range of products: from shoes to clothing, from ties to water bottles, even portable barbecues and camping chairs. It allows us to communicate a broader vision for the brand, just as we do with our Yearbook, creating an experience that goes beyond the simple act of purchasing a product.

We want customers not just to shop, but to immerse themselves in a culture that extends beyond the merchandise. For instance, we regularly update our in-store book selection, featuring titles on American national parks, sailing, and the history of Maine. Every visit to one of our stores should be a cultural experience, which is why we also host in-store events: to build a real community around the brand.

To me, a lifestyle store is like a microcosm that encapsulates everything a brand has to offer. We aim to create a complete experience. And it’s not just about clothing: in our stores, you’ll find items like artisanal soaps, books, and small souvenirs that all tell a story. It’s like traveling and bringing home something that reminds you of the place you’ve been. I personally love walking into a store without any intention to buy, and walking out with a small item – maybe a coin pouch or a magazine – that brings home a little piece of the brand’s culture.

What does the future hold for Sebago? Will the YEARBOOK project continue? Can we expect more initiatives diving into your history?

One of our upcoming releases will be a line of fragrances and soaps, which actually started from a chance encounter during a trip to New York. At a dinner, I met the CEO of a fragrance brand with a fascinating backstory connected to the U.S. Navy. That sparked the idea of a collaboration – including a classic “soap on a rope,” an American tradition that dates back to sailing life and college dorms and fits perfectly within Sebago’s world of sailing and outdoor living.

More broadly, we’re expanding our ready-to-wear offering. We recently showcased at Pitti Uomo, which was a strong signal of our strategy: we’ll continue to grow our core business – footwear – but always alongside a full, integrated look. These days, I dedicate a lot of time and energy to balancing the footwear and upperwear lines, which I believe is essential.

We also have smaller projects in the works, like the launch of a picnic mat coming out this April. It’s a product born from personal experience – when I go out to the countryside with my kids, I always find it hard to sit comfortably on wet grass. So we partnered with Original Madras, an Indian company, to create a picnic blanket made from Madras fabric with a waterproof middle layer. I’m genuinely excited about it – it has amazing colors and functionality that make it truly special. For me, it’s almost more meaningful than launching a new shoe, because it’s this attention to detail – these practical and even impractical objects – that completes the Sebago experience.

In a world where shoes and clothes can get lost in a sea of products, it’s the context around them that gives them value. And these small, everyday items, objects that blend into our lives, are what make our brand resonate on a deeper level.

As for the Sebago Yearbook, it will definitely continue. The next issue will follow the same philosophy, featuring new guests and compelling content. There’s one interview I’ve been looking forward to for a long time, and we’ll finally publish it: it features the president of our company, Marco Boglione. He’s been instrumental in the brand’s development and has a unique perspective on our journey. Sebago is in Italy today thanks to him. When we acquired the brand, the product had been weakened by years of multinational management that didn’t honor its original character. We had to rebuild it – traveling across America, rediscovering the original lasts, working on leather quality. Marco played a central role in all of it, and in this interview, he’ll share his point of view. It’s important to me that people understand the roots of our work – the reason why Sebago has become what it is today.